CHAPTER 5

The Short Leash

ILLUSTRATION:U.S.Navy Hospital Training Manual

Scroll down to read post or to read the rest of today's posts. To read special interest sections

click on relevant section or blog posts to right o fpost

One of the arguments that towing vessel management made in the early 1970s when they insisted that the Coast Guard not impose the traditional Master, Mate, and Pilot officer licensing regime on diesel towing vessels after

series of horrific accidents that impelled Congress to mandate the examination and licensing of towboat “operators”

in 1972. This was called the “short leash argument.” Towing company owners and managers argued that inland,

harbor, and coastwise towing vessels were given so much support from their shore side offices and available

contract service providers that more extensive knowledge of navigation, stability, national shipping laws and

regulations, and emergency medical practices common for most traditional Merchant Marine licensed officers were

not really necessary in the towing industry.

Much the same argument was put forward by the new offshore mineral

and oil industry in the Gulf of Mexico at the same time.

Management would change their tune years later when they realized that their “short leash” left management

holding the bag for liability in an accident because the law, as written, left them with a choice; they could either

hire a licensed Master and Pilot or one of the newly licensed towing vessel “operators.” Unfortunately for

management, they nearly always chose the lower-paid “operator” to maximize their profits.

Management, in the Congressional Record, described the relative lack of training for these “operators” and their

successful management of that risk by using the “short leash” to keep on top of things! When an unfortunate series

of major accidents started to happen from the 1993 Sunset Limited accident forward, management found itself

unable to take advantage of the “limitation of liability” provision in maritime law that allowed a ship owner to

avoid liability beyond the salvage value of his ship and its cargo in the wake of an accident caused by factors

beyond his “privity and knowledge.” By using licensed “operators,” the owners could no longer argue that they

had hired “licensed professionals” to run their vessels and that, as owners, they had no “privity and knowledge” of

any navigational or operational professional shortcomings their Captains may have had.

Needless to say following

several spectacular and expensive accidents, the easy-to-obtain “operator” class of license was regulated out of

existence and started to disappear between 2001 and 2006. Holders of the old “Operator” licenses were

“grandfathered” as Masters, Mates, or Pilots of towing vessels with licenses that became increasingly restricted to

domestic routes. Deckhands hopeful of obtaining a new towing license came up against a one-year apprenticeship

requirement and seriously enhanced experience, training, and professional examination requirements.

Yet even today, the vessel owners and their operating companies still argue the “short leash” as if the short leash

still existed when denying their officers and crewmembers first class emergency medical response on board

equipment and training.

Meet Capt. John LoCicero.

He Made His Own Splint with a Rolled Newspaper and Duct Tape;

Years After His Injury, He Cannot Use His Right Hand

[Source: Reported by Captain John LoCicero in several interviews.]

When Captain John LoCicero was an active member of our Association, he told us that ten years ago, he never

would have considered joining a mariner's association like ours, or a labor union. Back then, he believed that his

employer cared about him as a person and would take care of him if he was hurt on the job. He now admits that his

trust was misplaced and wants to tell his story to other mariners so they may avoid the same bitter experience.

A mariner needs to understand that there are two sides to many important health, safety, and welfare issues.

Although your boss may be a fine and honorable person you respect and enjoy working for, he is your employer

and his interests and concerns may not always coincide with yours. Although you owe him your loyalty as an

employee, there are times when you must put your interests and those of your family first and foremost.

In 1993, John was serving as relief captain on an uninspected towing vessel working on the Gulf Intracoastal

Waterway pushing tank barges between Louisiana and Texas. He was employed by the Frazier Towing Company,

a small mom-and-pop towing operation based in southeast Louisiana. On the voyage when he was injured, he was

working as Pilot under the direction of the son of the company's owner who served as the vessel's captain.

The tow consisted of one tank barge owned by Hollywood Marine – a customer of Frazier Towing Company.

While underway during a voyage in 1994, John tripped on the deck and injured his right wrist and arm and was

in severe pain. The boat's Captain called on Hollywood Marine for assistance. A Hollywood employee drove John

to a local Houston-area hospital where John's injured arm was examined. He was told his wrist was broken but that

the hospital's orthopedic specialist was not there to set it. Consequently, John was brought back to the towboat

even though he asked to be taken to another hospital for immediate emergency treatment. He was told that medical

treatment was the responsibility of his employer, the Frazier Towing Company, and not up to Hollywood Marine,

owner of the barge.

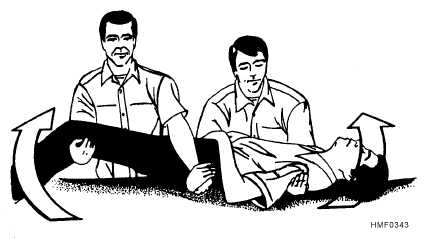

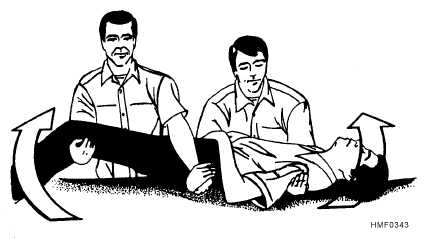

On returning to the boat, John was in severe pain and told the Captain that he thought he was going into shock.

Since the towboat was now tied to the dock at the refinery, the Captain called the refinery's emergency medical

technician (EMT) who arrived in an ambulance but did not even have a splint to immobilize the fracture. John

finally immobilized it himself by wrapping a newspaper around it and using duct tape to secure it. Since he could

not work because of the pain, he asked to be relieved.

Left to Suffer

Twenty-four hours later, John arrived by company carryall at Frazier Towing Company's parking lot on the bayou in

southeast Louisiana where he was dropped off at his parked car and left to fend for himself. He had received no

additional medical treatment and was still in severe pain. John put it this way: "I have hurt myself in the past, but I never

had pain like that in my life. I hurt so damn bad I can't even begin to tell anyone the pain I felt."

John was left with no alternative but to drive his car with one arm immobilized about 25 miles up the bayou to

Raceland and then on to his home forty miles further on in Metairie. He mmediately called the company office

and, being a Saturday, left a message for the Port Captain to call him with further instructions for medical care.

No Immediate Company Concern

On Sunday, the port captain never bothered to return his call. So, bright and early on Monday, John called the

office and spoke to the secretary. The secretary asked him why he was still walking around-with a broken arm.

John replied that the hospitals asked embarrassing questions about his medical coverage he could not answer and,

specifically, who was responsible for paying the bill. Eventually, the office appeared to settle the matter and sent

him to a doctor later in the day. The doctor gave him pain medicine, properly immobilized the arm, and because

the doctor was busy, gave him an appointment to come back in a week to get it set.

When John returned, he learned that his arm had suffered severe nerve damage and that it would require a major

operation using a nerve taken from his leg. The doctor scheduled the operation for the next day. However, when

John arrived for the operation, he was told that the company did not have the funds to pay for it and that it could not

be performed. Shortly thereafter, the company stopped paying his maintenance and cure. Four-and-a-half months

later, they were still talking about surgery but had not yet performed it.

No Surgery and Inadequate Settlement

John then hired an attorney who was only able to extract a small and unsatisfactory settlement from the

company. John can no longer work as a mariner. Eighteen years later, John has no use of his right hand

whatsoever and lives on small government disability payments.

Some Thoughts for Fellow Mariners

John's advice to his fellow mariners is this: "Watch your step. Be careful whom you work for. Be sure these

people can and will take care of you if you are hurt. Don't blindly accept what these companies tell you, because

they are all born liars. They'll tell you what you want to hear."

John asks our mariners consider these points:

● Are you working for a reputable employer that provides you and your family with adequate medical and disability

coverage?

● Has your employer ever cheated mariners that you know out of legitimate "maintenance and cure" payments?

● What type of medical coverage do you have today and how would it cover you under the same circumstances that

he faced in a distant city or even at home?

● Have you read the fine-print of your medical policy or do you need it explained to you?

● Do you carry the necessary credentials that will give you entry to an emergency room?

● Does your health coverage include transportation by ambulance if it is medically necessary?

● How soon will you be covered if you go to work for a new employer? If you have a 60 or 90 day waiting period,

how do you plan to protect yourself against possible medical bills that could bankrupt you?

● If you must sue your employer, does he carry enough insurance to pay you for your medical care, your time lost

from work, or for a disabling injury that lasts for the rest of your life? Would your employer fire you if you asked

these questions? If so, your relationship with your employer is fragile indeed.

In 1994, the Coast Guard determined that working on a towing vessel was nine times more dangerous than

working at an "average" job – even more dangerous than on a commercial fishing vessel.(1) With that in mind, do

you have a lawyer in mind that can represent your interests in the maritime environment? [(1)Refer to our Report

#R-351, Rev.1.]

As a post-script, John left this thought: "I wish I could make our guys understand that it's not the same world

anymore. Small companies are being swallowed up by big companies. Soon, only two or three big companies will

be left, and the little guy will not have much of a choice anymore. One mistake and you just won't work on boats

again – plain and simple. We are looking at a sweat-shop situation if we don't stand up, pitch in, and get noticed."

The comment that “…You just won’t work on boats again” refers to the practice of lacklisting” or

NMA Report #R-210 that explains the elaborate details.]

“blackballing” – a unfair labor practice that continues to end many seagoing careers. Our Association urged

Congress to amend 46 U.S. Code §2114, Protection Against Discrimination which they did in 2010.(1) [(1)Refer to

No comments:

Post a Comment